Lamento di Philip Roth/Appendice1

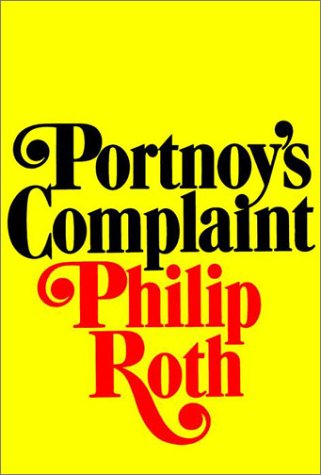

Portnoy’s Complaint

[modifica | modifica sorgente]Incipit

[modifica | modifica sorgente]Portnoy's Complaint (port/'noiz kam-plant') n. [after Alexander Portnoy (1933 )] A disorder in which strongly-felt ethical and altruistic impulses are perpetually warring with extreme sexual longings, often of a perverse nature. Spielvogel says: ‘Acts of exhibitionism, voyeurism, fetishism, auto-eroticism and oral coitus are plentiful; as a consequence of the patient's morality, however, neither fantasy nor act issues in genuine sexual gratification, but rather in overriding feelings of shame and the dread of retribution, particularly in the form of castration.’ (Spielvogel, O. The Puzzled Penis, Internationale Zeitschrift fur Psychoanalyse) Vol. XXIV p. 909.) It is believed by Spielvogel that many of the symptoms can be traced to the bonds obtaining in the mother-child relationship.

THE MOST UNFORGETTABLE CHARACTER I'VE MET

[modifica | modifica sorgente]She was so deeply imbedded in my consciousness that for the first year of school I seem to have believed that each of my teachers was my mother in disguise. As soon as the last bell had sounded, I would rush off for home, wondering as I ran if I could possibly make it to our apartment before she had succeeded in transforming herself. Invariably she was already in the kitchen by the time I arrived, and setting out my milk and cookies. Instead of causing me to give up my delusions, however, the feat merely intensified my respect for her powers. And then it was always a relief not to have caught her between incarnations anyway- even if I never stopped trying; I knew that my father and sister were innocent of my mother's real nature, and the burden of betrayal that I imagined would fall to me if I ever came upon her unawares was more than I wanted to bear at the age of five. I think I even feared that I might have to be done away with were I to catch sight of her flying in from school through the bedroom window, or making herself emerge, limb by limb, out of an invisible state and into her apron.

Of course, when she asked me to tell her all about my day at kindergarten, I did so scrupulously. I didn't pretend to understand all the implications of her ubiquity, but that it had to do with finding out the kind of little boy I was when I thought she wasn't around-that was indisputable. One consequence of this fantasy, which survived (in this particular form) into the first grade, was that seeing as I had no choice, I became honest.

Ah, and brilliant. Of my sallow, overweight older sister, my mother would say (in Hannah's presence, of course: honesty was her policy too), The child is no genius, but then we don't ask the impossible. God bless her, she works hard, she applies herself to her limits, and so whatever she gets is all right. Of me, the heir to her long Egyptian nose and clever babbling mouth, of me my mother would say, with characteristic restraint, This bonditt? He doesn't even have to open a book- 'A' in everything. Albert Einstein the Second!

And how did my father take all this? He drank- of course, not whiskey like a goy, but mineral oil and milk of magnesia; and chewed on Ex-Lax; and ate All-Bran morning and night; and downed mixed dried fruits by the pound bag. He suffered- did he suffer! - from constipation. Her ubiquity and his constipation, my mother flying in through the bedroom window, my father reading the evening paper with a suppository up his ass . . . these, Doctor, are the earliest impressions I have of my parents, of their attributes and secrets. He used to brew dried senna leaves in a saucepan, and that, along with the suppository melting invisibly in his rectum, comprised his witchcraft: brewing those vein green leaves, stirring with a spoon the evil-smelling liquid, then carefully pouring it into a strainer, and hence into his blockaded body, through that weary and afflicted expression on his face. And then hunched silently above the empty glass, as though listening for distant thunder, he awaits the miracle . . . As a little boy I sometimes sat in the kitchen and waited with him. But the miracle never came, not at least as we imagined and prayed it would, as a lifting of the sentence, a total deliverance from the plague. I remember that when they announced over the radio the explosion of the first atom bomb, he said aloud, Maybe that would do the job. But all catharses were in vain for that man: his kishkas were gripped by the iron hand of outrage and frustration. Among his other misfortunes, I was his wife's favorite.

To make life harder, he loved me himself. He too saw in me the family's opportunity to be as good as anybody, our chance to win honor and respectthough when I was small the way he chose to talk of his ambitions for me was mostly in terms of money. Don't be dumb like your father, he would say, joking with the little boy on his lap, don't marry beautiful, don't marry love-marry rich. No, no, he didn't like being looked down upon one bit. Like a dog he workedonly for a future that he wasn't slated to have. Nobody ever really gave him satisfaction, return commensurate with goods delivered- not my mother, not me, not even my loving sister, whose husband he still considers a Communist (though he is a partner today in a profitable soft-drink business, and owns his own home in West Orange). And surely not that billion-dollar Protestant outfit (or institution, as they prefer to think of themselves) by whom he was exploited to the full. 'The Most Benevolent Financial Institution in America I remember my father announcing, when he took me for the first time to see his little square area of desk and chair in the vast offices of Boston Northeastern Life. Yes, before his son he spoke with pride of The Company ; no sense demeaning himself by knocking them in public-after all, they had paid him a wage during the Depression; they gave him stationery with his own name printed beneath a picture of the May flower, their insignia ( and by extension his, ha ha); and every spring, in the fullness of their benevolence, they sent him and my mother for a hotsy-totsy free weekend in Atlantic City, to a fancy goyische hotel no less, there (along with all the other insurance agents in the Middle Atlantic states who had exceeded the A.E.S., their annual expectation of sales) to be intimidated by the desk clerk, the waiter, the bellboy, not to mention the puzzled paying guests.

Also, he believed passionately in what he was selling, yet another source of anguish and drain upon his energies.

He wasn't lust saving his own soul when he donned his coat and hat after dinner and went out again to resume his work-no, it was also to save some poor son of a bitch on the brink of letting his insurance policy lapse, and thus endangering his family's security in the event of a rainy day. Alex, he used to explain to me, a man has got to have an umbrella for a rainy day. You don't leave a wife and a child out in the rain without an umbrella! And though to me, at five and six years of age, what he said made perfect, even moving, sense, that apparently was not always the reception his rainy-day speech received from the callow Poles, and violent Irishmen, and illiterate Negroes who lived in the impoverished districts that had been given him to canvass by The Most Benevolent Financial Institution in America.

They laughed at him, down in the slums. They didn't listen. They heard him knock, and throwing their empties against the door, called out, Go away, nobody home. They set their dogs to sink their teeth into his persistent Jewish ass. And still, over the years, he managed to accumulate from The Company enough plaques and scrolls and medals honoring his salesmanship to cover an entire wall of the long windowless hallway where our Passover dishes were stored in cartons and our Oriental rugs lay mummified in their thick wrappings of tar paper over the summer. If he squeezed blood from a stone, wouldn't The Company reward him with a miracle of its own? Might not The President up in The Home Office get wind of his accomplishment and turn him overnight from an agent at five thousand a year to a district manager at fifteen? But where they had him they kept him. Who else would work such barren territory with such incredible results? Moreover, there had not been a Jewish manager in the entire history of Boston Northeastern (Not Quite Our Class, Dear, as they used to say on the Mayflower), and my father, with his eighth-grade education, wasn't exactly suited to be the Jackie Robinson of the insurance business.

N. Everett Lindabury, Boston Northeastern's president, had his picture hanging in our hallway. The framed photograph had been awarded to my father after he had sold his first million dollars' worth of insurance, or maybe that's what came after you hit the ten-million mark. Mr. Lindabury, 'The Home Office . . . my father made it sound to me like Roosevelt in the White House in Washington . . . and all the while how he hated their guts, Lindabury's particularly, with his corn-silk hair and his crisp New England speech, the sons in Harvard College and the daughters in finishing school, oh the whole pack of them up there in Massachusetts, shkotzim fox-hunting! playing polo! (sol heard him one night, bellowing behind his bedroom door)- and thus keeping him, you see, from being a hero in the eyes of his wife and children. What wrath! What fury! And there was really no one to unleash it on-except himself. Why can't I move my bowels- I'm up to my ass in prunes! Why do I have these headaches! Where are my glasses! Who took my hat!

In that ferocious and self-annihilating way in which so many Jewish men of his generation served their families, my father served my mother, my sister Hannah, but particularly me. Where he had been imprisoned, I would fly: that was his dream. Mine was its corollary: in my liberation would be his- from ignorance, from exploitation, from anonymity. To this day our destinies remain scrambled together in my imagination, and there are still too many times when, upon reading in some book a passage that impresses me with its logic or its wisdom, instantly, involuntarily, I think, If only he could read this. Yes! Read, and understand- ! Still hoping, you see, still if- onlying, at the age of thirty-three . . . Back in my freshman year of college, when I was even more the son struggling to make the father understand- back when it seemed that it was either his understanding or his life I remember that I tore the subscription blank out of one of those intellectual journals I had myself just begun to discover in the college library, filled in his name and our home address, and sent off an anonymous gift subscription. But when I came sullenly home at Christmastime to visit and condemn, the Partisan Review was nowhere to be found. Colliers, Hygeia, Look, but where was his Partisan Review? Thrown out unopened- I thought in my arrogance and heartbreak-discarded unread, considered junk-mail by this schmuck, this moron, this Philistine father of mine!

I remember-to go back even further in this history of disenchantment-I remember one Sunday morning pitching a baseball at my father, and then waiting in vain to see it go flying off, high above my head. I am eight, and for my birthday have received my first mitt and hardball, and a regulation bat that I haven't even the strength to swing all the way around. My father has been out since early morning in his hat, coat, bow tie, and black shoes, carrying under his arm the massive black collection book that tells who owes Mr. Lindabury how much. He descends into the colored neighborhood each and every Sunday morning because, as he tells me, that is the best time to catch those unwilling to fork over the ten or fifteen measly cents necessary to meet their weekly premium payments. He lurks about where the husbands sit out in the sunshine, trying to extract a few thin dimes from them before they have drunk themselves senseless on their bottles of Morgan Davis wine; he emerges from alleyways like a shot to catch between home and church the pious cleaning ladies, who are off in other people's houses during the daylight hours of the week, and in hiding from him on weekday nights. Uh--oh, someone cries, Mr. Insurance Man here! and even the children run for cover- the children, he says in disgust, so tell me, what hope is there for these niggers' ever improving their lot? How will they ever lift themselves if they ain't even able to grasp the importance of life insurance? Don't they give a single crap for the loved ones they leave behind? Because they's all going to die too, you know- oh, he says angrily, 'they she' is!' Please, what kind of man is it, who can think to leave children out in the rain without even a decent umbrella for protection!

We are on the big dirt field back of my school. He sets his collection book on the ground, and steps up to the plate in his coat and his brown fedora. He wears square steel-rimmed spectacles, and his hair (which now I wear) is a wild bush the color and texture of steel wool; and those teeth, which sit all night long in a glass in the bathroom smiling at the toilet bowl, now smile out at me, his beloved, his flesh and his blood, the little boy upon whose head no rain shall ever fall. Okay, Big Shot Ballplayer, he says, and grasps my new regulation bat somewhere near the middle-and to my astonishment, with his left hand where his right hand should be. I am suddenly overcome with such sadness: I want to tell him, Hey, your hands are wrong, but am unable to, for fear I might begin to cryor he might! Come on. Big Shot, throw the ball, he calls, and so I do- and of course discover that on top of all the other things I am just beginning to suspect about my father, he isn't King Kong Charlie Keller either.

Some umbrella.

It was my mother who could accomplish anything, who herself had to admit that it might even be that she was actually too good. And could a small child with my intelligence, with my powers of observation, doubt that this was so? She could make jello, for instance, with sliced peaches hanging in it, peaches just suspended there, in defiance of the law of gravity. She could bake a cake that tasted like a banana. Weeping, suffering, she grated he own horseradish rather than buy the pishachs they sold in a bottle at the delicatessen. She watched the butcher, as she put it, like a hawk, to be certain that he did not forget to put her chopped meat through the kosher grinder. She would telephone all the other women in the building drying clothes on the back lines- called even the divorced goy on the top floor one magnanimous day- to tell them rush, take in the laundry, a drop of rain had fallen on our windowpane. What radar on that woman! And this is before radar! The energy on her! The thoroughness! For mistakes she checked my sums; for holes, my socks; for dirt, my nails, my neck, every seam and crease of my body. She even dredges the furthest recesses of my ears by pouring cold peroxide into my head. It tingles and pops like an earful of ginger ale, and brings to the surface, in bits and pieces, the hidden stores of yellow wax, which can apparently endanger a person's hearing. A medical procedure like this (crackpot though it may be) takes time, of course; it takes effort, to be sure-but where health and cleanliness are concerned, germs and bodily secretions, she will not spare herself and sacrifice others. She lights candles for the dead-others invariably forget, she religiously remembers, and without even the aid of a notation on the calendar. Devotion is just in her blood. She seems to be the only one, she says, who when she goes to the cemetery has the common sense, the ordinary common decency, to clear the weeds from the graves of our relatives. The first bright day of spring, and she has mothproofed everything wool in the house, rolled and bound the rugs, and dragged them off to my father's trophy room. She is never ashamed of her house: a stranger could walk in and open any closet, any drawer, and she would have nothing to be ashamed of. You could even eat off her bathroom floor, if that should ever become necessary. When she loses at mah-jongg she takes it like a sport, not-like-the-others-whose-namesshe- could-mention-but-she-won't-not-even-Tilly-Hochman-it's-too-petty-toeven- talk-about-lets-just-forget-she-even-brought -it- up. She sews, she knits, she darns- she irons better even than the schvartze, to whom, of all her friends who each possess a piece of this grinning childish black old lady's hide, she alone is good. I'm the only one who's good to her. I'm the only one who gives her a whole can of tuna for lunch, and Im not talking dreck, either, Im talking Chicken of the Sea, Alex. I'm sorry, I can't be a stingy person. Excuse me, but I can't live like that, even if it is 2 for 49₢ Esther Wasserberg leaves twenty-five cents in nickels around the house when Dorothy comes, and counts up afterwards to see it's all there. Maybe I'm too good, she whispers to me, meanwhile running scalding water over the dish from which the cleaning lady has just eaten her lunch, alone like a leper, but I couldn't do a thing like that. Once Dorothy chanced to come back into the kitchen while my mother was still standing over the faucet marked H, sending torrents down upon the knife and fork that had passed between the schvartze’s thick pink lips. Oh, you know how hard it is to get mayonnaise off silverware these days, Dorothy, says my nimbletongued mother- and thus, she tells me later, by her quick thinking, has managed to spare the colored woman's feelings.

When I am bad I am locked out of the apartment. I stand at the door hammering and hammering until I swear I will turn over a new leaf. But what is it I have done? I shine my shoes every evening on a sheet of last night's newspaper laid carefully over the linoleum; afterward I never fail to turn securely the lid on the tin of polish, and to return all the equipment to where it belongs. I roll the toothpaste tube from the bottom, I brush my teeth in circles and never up and down, I say Thank you, I say You're welcome, I say I beg your pardon, and May I. When Hannah is ill or out before supper with her blue tin can collecting for the Jewish National Fund, I voluntarily and out of my turn set the table, remembering always knife and spoon on the right, fork on the left, and napkin to the left of the fork and folded into a triangle. I would never eat milchiks off a flaishedigeh dish, never, never, never. Nonetheless, there is a year or so in my life when not a month goes by that I don't do something so inexcusable that I am told to pack a bag and leave. But what could it possibly be? Mother, it's me, the little boy who spends whole nights before school begins beautifully lettering in Old English script the names of his subjects on his colored course dividers, who patiently fastens reinforcements to a term's worth of three-ringed paper, lined and unlined both. I carry a comb and a clean hankie; never do my knicker stockings drag at my shoes, I see to that; my homework is completed weeks in advance of the assignment- let's face it, Ma, I am the smartest and neatest little boy in the history of my school! Teachers (as you know, as they have told you) go home happy to their husbands because of me. So what is it I have done? Will someone with the answer to that question please stand up! I am so awful she will not have me in her house a minute longer. When I once called my sister a cocky-doody, my mouth was immediately washed with a cake of brown laundry soap; this I understand. But banishment? What can I possibly have done!

Because she is good she will pack a lunch for me to take along, but then out I go, in my coat and my galoshes, and what happens is not her business.

Okay, I say, if that's how you feel! (For I have the taste for melodrama too- I am not in this family for nothing. ) I don't need a bag of lunch! I don't need anything!

I don't love you any more, not a little boy who behaves like you do. I'll live alone here with Daddy and Hannah, says my mother (a master really at phrasing things just the right way to kill you). Hannah can set up the mah-jongg tiles for the ladies on Tuesday night. We won't be needing you any more.

Who cares! And out the door I go, into the long dim hallway. Who cares! I will sell newspapers on the streets in my bare feet. I will ride where I want on freight cars and sleep in open fields, I think-and then it is enough for me to see the empty milk bottles standing by our welcome mat, for the immensity of all I have lost to come breaking over my head. I hate you! I holler, kicking a galosh at the door; you stink! To this filth, to this heresy booming through the corridors of the apartment building where she is vying with twenty other Jewish women to be the patron saint of self-sacrifice, my mother has no choice but to throw the double-lock on our door. This is when I start to hammer to be let in. I drop to the doormat to beg forgiveness for my sin (which is what again?) and promise her nothing but perfection for the rest of our lives, which at that time I believe will be endless.

Then there are the nights I will not eat. My sister, who is four years my senior, assures me that what I remember is fact: I would refuse to eat, and my mother would find herself unable to submit to such willfulness- and such idiocy. And unable to for my own good. She is only asking me to do something for my own good- and still I say no? Wouldn't she give me the food out of her own mouth, don't I know that by now?

But I don't want the food from her mouth. I don't even want the food from my plate- that's the point.

Please! a child with my potential! my accomplishments! my future!- all the gifts God has lavished upon me, of beauty, of brains, am I to be allowed to think I can just starve myself to death for no good reason in the world? Do I want people to look down on a skinny little boy all my life, or to look up to a man?

Do I want to be pushed around and made fun of, do I want to be skin and bones that people can knock over with a sneeze, or do I want to command respect?

Which do I want to be when I grow up, weak or strong, a success or a failure, a man or a mouse?

I just don't want to eat, I answer.

So my mother sits down in a chair beside me with a long bread knife in her hand. It is made of stainless steel, and has little sawlike teeth. Which do I want to be, weak or strong, a man or a mouse?

Doctor, why, why oh why oh why oh why does a mother pull a knife on her own son? I am six, seven years old, how do I know she really wouldn't use it? What am I supposed to do, try bluffing her out, at seven? I have no complicated sense of strategy, for Christ's sake- I probably don't even weigh sixty pounds yet! Someone waves a knife in my direction, I believe there is an intention lurking somewhere to draw my blood! Only why? What can she possibly be thinking in her brain? How crazy can she possibly be? Suppose she had let me win- what would have been lost? Why a knife, why the threat of murder, why is such total and annihilating victory necessary- when only the day before she set down her iron on the ironing board and applauded as I stormed around the kitchen rehearsing my role as Christopher Columbus in the thirdgrade production of Land Ho! I am the star actor of my class, they cannot put a play on without me. Oh, once they tried, when I had my bronchitis, but my teacher later confided in my mother that it had been decidedly second-rate. Oh how, how can she spend such glorious afternoons in that kitchen, polishing silver, chopping liver, threading pew elastic in the waistband of my little jockey shorts- and feeding me all the while my cues from the mimeographed script, playing Queen Isabella to my Columbus, Betsy Ross to my Washington, Mrs. Pasteur to my Louis- how can she rise with me on the crest of my genius during those dusky beautiful hours after school, and then at night, because I will not eat some string beans and a baked potato, point a bread knife at my heart?

And why doesn't my father stop her?

WHACKING OFF

[modifica | modifica sorgente]Then came adolescence-half my waking life spent locked behind the bathroom door, firing my wad down the toilet bowl, or into the soiled clothes in the laundry hamper, or splat, up against the medicine-chest mirror, before which I stood in my dropped drawers so I could see how it looked coming out. Or else I was doubled over my flying fist, eyes pressed closed but mouth wide open, to take that sticky sauce of buttermilk and Clorox on my own tongue and teeththough not infrequently, in my blindness and ecstasy, I got it all in the pompadour, like a blast of Wildroot Cream Oil. Through a world of matted handkerchiefs and crumpled Kleenex and stained pajamas, I moved my raw and swollen penis, perpetually in dread that my loathsomeness would be discovered by someone stealing upon me just as I was in the frenzy of dropping my load. Nevertheless, I was wholly incapable of keeping my paws from my dong once it started the climb up my belly. In the middle of a class I would raise a hand to be excused, rush down the corridor to the lavatory, and with ten or fifteen savage strokes, beat off standing up into a urinal. At the Saturday afternoon movie I would leave my friends to go off to the candy machine-and wind up in a distant balcony seat, squirting my seed into the empty wrapper from a Mounds bar. On an outing of our family association, I once cored an apple, saw to my astonishment (and with the aid of my obsession) what it looked like, and ran off into the woods to fall upon the orifice of the fruit, pretending that the cool and mealy hole was actually between the legs of that mythical being who always called me Big Boy when she pleaded for what no girl in all recorded history had ever had. Oh shove it in me, Big Boy, cried the cored apple that I banged silly on that picnic. Big Boy, Big Boy, oh give me all you've got, begged the empty milk bottle that I kept hidden in our storage bin in the basement, to drive wild after school with my vaselined upright. Come, Big Boy, come, screamed the maddened piece of liver that, in my own insanity, I bought one afternoon at a butcher shop and, believe it or not, violated behind a billboard on the way to a bar mitzvah lesson.

It was at the end of my freshman year of high school-and freshman year of masturbating-that I discovered on the underside of my penis, just where the shaft meets the head, a little discolored dot that has since been diagnosed as a freckle. Cancer. I had given myself cancer. All that pulling and tugging at my own flesh, all that friction, had given me an incurable disease. And not yet fourteen! In bed at night the tears rolled from my eyes. No! I sobbed. I don't want to die! Please-no! But then, because I would very shortly be a corpse anyway, I went ahead as usual and jerked off into my sock. I had taken to carrying the dirty socks into bed with me at night so as to be able to use one as a receptacle upon retiring, and the other upon awakening.

If only I could cut down to one hand-job a day, or hold the line at two, or even three! But with the prospect of oblivion before me, I actually began to set new records for myself. Before meals. After meals. During meals. Jumping up from the dinner table, I tragically clutch at my belly-diarrhea! I cry, I have been stricken with diarrhea!- and once behind the locked bathroom door, slip over my head a pair of underpants that I have stolen from my sister's dresser and carry rolled in a handkerchief in my pocket. So galvanic is the effect of cotton panties against my mouth- so galvanic is the word panties - that the trajectory of my ejaculation reaches startling new heights: leaving my joint like a rocket it makes right for the light bulb overhead, where to my wonderment and horror, it hits and it hangs. Wildly in the first moment I cover my head, expecting an explosion of glass, a burst of flames- disaster, you see, is never far from my mind. Then quietly as I can I climb the radiator and remove the sizzling gob with a wad of toilet paper. I begin a scrupulous search of the shower curtain, the tub, the tile floor, the four tooth-brushes- God forbid!- and just as I am about to unlock the door, imagining I have covered my tracks, my heart lurches at the sight of what is hanging like snot to the toe of my shoe. I am the Raskolnikov of jerking offthe sticky evidence is everywhere! Is it on my cuffs too? in my hair? my ear? All this I wonder even as I come back to the kitchen table, scowling and cranky, to grumble self-righteously at my father when he opens his mouth full of red jello and says, I don't understand what you have to lock the door about. That to me is beyond comprehension. What is this, a home or a Grand Central station? . . . privacy . . . a human being . . . around here never, I reply, then push aside my dessert to scream, I don't feel well- will everybody leave me alone?

After dessert-which I finish because I happen to like jello, even if I detest them-after dessert I am back in the bathroom again. I burrow through the week's laundry until I uncover one of my sister's soiled brassieres. I string one shoulder strap over the knob of the bathroom door and the other on the knob of the linen closet: a scarecrow to bring on more dreams. Oh beat it, Big Boy, beat it to a red-hot pulp- so I am being urged by the little cups of Hannah's brassiere, when a rolled-up newspaper smacks at the door. And sends me and my handful an inch off the toilet seat. - Come on, give somebody else a crack at that bowl, will you? my father says. I haven't moved my bowels in a week.

I recover my equilibrium, as is my talent, with a burst of hurt feelings. I have a terrible case of diarrhea! Doesn't that mean anything to anyone in this house? - in the meantime resuming the stroke, indeed quickening the tempo as my cancerous organ miraculously begins to quiver again from the inside out.

Then Hannah's brassiere begins to move. To swing to and fro! I veil my eyes, and behold!- Lenore Lapidus! who has the biggest pair in my class, running for the bus after school, her great untouchable load shifting weightily inside her blouse, oh I urge them up from their cups, and over, LENORE LAPIDUS'S ACTUAL TITS, and realize in the same split second that my mother is vigorously shaking the doorknob. Of the door I have finally forgotten to lock! I knew it would happen one day! Caught! As good as dead!

Open up, Alex. I want you to open up this instant.

It's locked, I'm not caught! And I see from what's alive in my hand that I'm not quite dead yet either. Beat on then! beat on! Lick me, Big Boy-lick me a good hot lick! I'm Lenore Lapidus's big fat red-hot brassiere!

Alex, I want an answer from you. Did you eat French fries after school? Is that why you're sick like this?

Nuhhh, nuhhh.

Alex, are you in pain? Do you want me to call the doctor? Are you in pain, or aren't you? I want to know exactly where it hurts. Answer me.

Yuhh, yuhhh-

Alex, I don't want you to flush the toilet, says my mother sternly. I want to see what you've done in there. I don't like the sound of this at all.

And me, says my father, touched as he always was by my accomplishments-as much awe as envy- I haven't moved my bowels in a week, just as I lurch from my perch on the toilet seat, and with the whimper of a whipped animal, deliver three drops of something barely viscous into the tiny piece of cloth where my flat-chested eighteen-year-old sister has laid her nipples, such as they are. It is my fourth orgasm of the day. When will I begin to come blood?

Get in here, please, you, says my mother. Why did you flush the toilet when I told you not to?

I forgot.

What was in there that you were so fast to flush it?

Diarrhea.

Was it mostly liquid or was it mostly poopie?

I don't look! I didn't look! Stop saying poopie to me- I'm in high school!

Oh, don't you shout at me, Alex. I'm not the one who gave you diarrhea, I assure you. If all you ate was what you were fed at home, you wouldn't be running to the bathroom fifty times a day. Hannah tells me what you're doing, so don't think I don't know.

She's missed the underpants! I’ve been caught! Oh, let me be dead! I'd just as soon!

Yeah, what do I do . . . ?

You go to Harold's Hot Dog and Chazerai Palace after school and you eat French fries with Melvin Weiner. Don't you? Don't lie to me either. Do you or do you not stuff yourself with French fries and ketchup on Hawthorne Avenue after school? ack, come in here, I want you to hear this, she calls to my father, now occupying the bathroom.

Look, I'm trying to move my bowels, he replies. Don't I have enough trouble as it is without people screaming at me when I'm trying to move my bowels?

You know what your son does after school, the A student, who his own mother can't say poopie to anymore, he's such a grown-up? What do you think your grown-up son does when nobody is watching him?

Can I please be left alone, please? cries my father. Can I have a little peace, please, so I can get something accomplished in here?

Just wait till your father hears what you do, in defiance of every health habit there could possibly be. Alex, answer me something. You're so smart, you know all the answers now, answer me this: how do you think Melvin Weiner gave himself colitis? Why has that child spent half his life in hospitals?

Because he eats chazerai,

Don't you dare make fun of me!

All right, I scream, how did he get colitis?

Because he eats chazerai! But it's not a joke! Because to him a meal is an O Henry bar washed down by a bottle of Pepsi. Because his breakfast consists of, do you know what? The most important meal of the day- not according just to your mother, Alex, but according to the highest nutritionists-and do you know what that child eats?

A doughnut.

A doughnut is right, Mr. Smart Guy, Mr. Adult. And coffee. Coffee and a doughnut, and on this a thirteen-year-old pisher with half a stomach is supposed to start a day. But you, thank God, have been brought up differently. You don't have a mother who gallivants all over town like some names I could name, from Barn's to Hahne's to Kresge's all day long. Alex, tell me, so it's not a mystery, or maybe I'm just stupid-only tell me, what are you trying to do, what are you trying to prove, that you should stuff yourself with such junk when you could come home to a poppyseed cookie and a nice glass of milk? I want the truth from you. I wouldn't tell your father, she says, her voice dropping significantly, but I must have the truth from you. Pause. Also significant. Is it just French fries, darling, or is it more? . . . Tell me, please, what other kind of garbage you're putting into your mouth so we can get to the bottom of this diarrhea! I want a straight answer from you, Alex. Are you eating hamburgers out? Answer me, please, is that why you flushed the toilet- was there hamburger in it?

I told you- I don't look in the bowl when I flush it! I'm not interested like You are in other people's poopie!

Oh, oh, oh- thirteen years old and the mouth on him! To someone who is asking a question about his health, his welfare! The utter incomprehensibility of the situation causes her eyes to become heavy with tears. Alex, why are you getting like this, give me some clue? Tell me please what horrible things we have done to you all our lives that this should be our reward? I believe the question strikes her as original. I believe she considers the question unanswerable. And worst of all, so do I. What have they done for me all their lives, but sacrifice? Yet that this is precisely the horrible thing is beyond my understanding- and still, Doctor! To this day!

I brace myself now for the whispering. I can spot the whispering coming a mile away. We are about to discuss my father's headaches.

Alex, he didn't have a headache on him today that he could hardly see straight from it? She checks, is he out of earshot? God forbid he should hear how critical his condition is, he might claim exaggeration. He's not going next week for a test for a tumor?

He is?

'Bring him in,' the doctor said, 'I'm going to give him a test for a tumor.' Success. I am crying. There is no good reason for me to be crying, but in this household everybody tries to get a good cry in at least once a day. My father, you must understand- as doubtless you do: blackmailers account for a substantial part of the human community, and, I would imagine, of your clientele- my father has been going for this tumor test for nearly as long as I can remember. Why his head aches him all the time is, of course, because he is constipated all the timewhy he is constipated is because ownership of his intestinal tract is in the hands of the firm of Worry, Fear Frustration. It is true that a doctor once said to my mother that he would give her husband a test for a tumor- if that would make her happy, is I believe the way that he worded it; he suggested that it would be cheaper, however, and probably more effective for the man to invest in an enema bag. Yet, that I know all this to be so, does not make it any less heartbreaking to imagine my father's skull splitting open from a malignancy.

Yes, she has me where she wants me, and she knows it. I clean forget my own cancer in the grief that comes- comes now as it came then- when I think how much of life has always been ( as he himself very accurately puts it ) beyond his comprehension. And his grasp. No money, no schooling, no language, no learning, curiosity without culture, drive without opportunity, experience without wisdom . . . How easily his inadequacies can move me to tears. As easily as they move me to anger!

A person my father often held up to me as someone to emulate in life was the theatrical producer Billy Rose. Walter Winchell said that Billy Rose's knowledge of shorthand had led Bernard Baruch to hire him as a secretaryconsequently my father plagued me throughout high school to enroll in the shorthand course. Alex, where would Billy Rose be today without his shorthand? Nowhere! So why do you fight me? Earlier it was the piano we battled over. For a man whose house was without a phonograph or a record, he was passionate on the subject of a musical instrument. I don't understand why you won't take a musical instrument, this is beyond comprehension. Your little cousin Toby can sit down at the piano and play whatever song you can name. All she has to do is sit at the piano and play Tea for Two' and everybody in the room is her friend. She'll never lack for companionship, Alex, shell never lack for popularity. Only tell me you'll take up the piano, and I'll have one in here tomorrow morning. Alex, are you listening to me? I am offering you something that could change the rest of your life!

But what he had to offer I didn't want- and what I wanted he didn't have to offer. Yet how unusual is that? Why must it continue to cause such pain? At this late date! Doctor, what should I rid myself of, tell me, the hatred . . . or the love? Because I haven't even begun to mention everything I remember with pleasure - I mean with a rapturous, biting sense of loss! All those memories that seem somehow to be bound up with the weather and the time of day, and that flash into mind with such poignancy, that momentarily I am not down in the subway, or at my office, or at dinner with a pretty girl, but back in my childhood, with them. Memories of practically nothing- and yet they seem moments of history as crucial to my being as the moment of my conception; I might be remembering his sperm nosing into her ovum, so piercing is my gratitude- yes, my gratitude!- so sweeping and unqualified is my love. Yes, me, with sweeping and unqualified love! I am standing in the kitchen ( standing maybe for the first time in my life ), my mother points, Look outside, baby, and I look; she says, See? how purple? a real fall sky The first line of poetry I ever hear! And I remember it! A real fall sky . . . It is an iron-cold January day, dusk- oh, these memories of dusk are going to kill me yet, of chicken fat on rye bread to tide me over to dinner, and the moon already outside the kitchen window- I have just come in with hot red cheeks and a dollar I have earned shoveling snow: You know what you're going to have for dinner, my mother coos so lovingly to me, for being such a hard-working boy? Your favorite winter meal. Lamb stew. It is night: after a Sunday in New York City, at Radio City and Chinatown, we are driving home across the George Washington Bridge-the Holland Tunnel is the direct route between Pell Street and Jersey City, but I beg for the bridge, and because my mother says it's educational, my father drives some ten miles out of his way to get us home. Up front my sister counts aloud the number of supports upon which the marvelous educational cables rest, while in the back I fall asleep with my face against my mother's black sealskin coat. At Lakewood, where we go one winter for a weekend vacation with my parents' Sunday night Gin Rummy Club, I sleep in one twin bed with my father, and my mother and Hannah curl up together in the other. At dawn my father awakens me and like convicts escaping, we noiselessly dress and slip out of the room. Come, he whispers, motioning for me to don my earmuffs and coat, I want to show you something. Did you know I was a waiter in Lakewood when I was sixteen years old? Outside the hotel he points across to the beautiful silent woods. How's that? he says. We walk together- at a brisk pace -around a silver lake. 'Take good deep breaths. Take in the piney air all the way. This is the best air in the world, good winter piney air. Good winter piney air- another poet for a parent! I couldn't be more thrilled if I were Wordsworth's kid! . . . In summer he remains in the city while the three of us go off to live in a furnished room at the seashore for a month. He will join us for the last two weeks, when he gets his vacation . . . there are times, however, when Jersey City is so thick with humidity, so alive with the mosquitoes that come dive-bombing in from the marshes, that at the end of his day's work he drives sixty-five miles, taking the old Cheesequake Highway- the Cheesequake! My God! the stuff you uncover here!- drives sixtyfive miles to spend the night with us in our breezy room at Bradley Beach.

He arrives after we have already eaten, but his own dinner waits while he unpeels the soggy city clothes in which he has been making the rounds of his debit all day, and changes into his swimsuit. I carry his towel for him as he clops down the street to the beach in his unlaced shoes. I am dressed in clean short pants and a spotless polo shirt, the salt is showered off me, and my hair- still my little boy's pre-steel wool hair, soft and combable - is beautifully parted and slicked down. There is a weathered iron rail that runs the length of the boardwalk, and I seat myself upon it; below me, in his shoes, my father crosses the empty beach. I watch him neatly set down his towel near the shore. He places his watch in one shoe, his eyeglasses in the other, and then he is ready to make his entrance into the sea. To this day I go into the water as he advised: plunge the wrists in first, then splash the underarms, then a handful to the temples and the back of the neck . . . ah, but slowly, always slowly. This way you get to refresh yourself, while avoiding a shock to the system. Refreshed, unshocked, he turns to face me, comically waves farewell up to where he thinks I'm standing, and drops backward to float with his arms outstretched. Oh he floats so still- he works, he works so hard, and for whom if not for me?- and then at last, after turning on his belly and making with a few choppy strokes that carry him nowhere, he comes wading back to shore, his streaming compact torso glowing from the last pure spikes of light driving in, over my shoulder, out of stifling inland New Jersey, from which I am being spared.

And there are more memories like this one. Doctor. A lot more. This is my mother and father I'm talking about.

But-but-but-let me pull myself together- there is also this vision of him emerging from the bathroom, savagely kneading the back of his neck and sourly swallowing a belch. All right, what is it that was so urgent you couldn't wait till I came out to tell me?

Nothing, says my mother. It's settled.

He looks at me, so disappointed. I'm what he lives for, and I know it. What did he do?

What he did is over and done with, God willing. You, did you move your bowels? she asks him.

Of course I didn't move my bowels.

Jack, what is it going to be with you, with those bowels?

They're turning into concrete, that's what it's going to be.

Because you eat too fast.

I don't eat too fast.

How then, slow?

I eat regular.

You eat like a pig, and somebody should tell you.

Oh, you got a wonderful way of expressing yourself sometimes, do you know that?

I'm only speaking the truth, she says. I stand on my feet all day in this kitchen, and you eat like there's a fire somewhere, and this one- this one has decided that the food I cook isn't good enough for him. He'd rather be sick and scare the living daylights out of me.

What did he do?

I don't want to upset you, she says. Let's just forget the whole thing. But she can't, so now she begins to cry. Look, she is probably not the happiest person in the world either. She was once a tall stringbean of a girl whom the boys called Red in high school. When I was nine and ten years old I had an absolute passion for her high school yearbook. For a while I kept it in the same drawer with that other volume of exotica, my stamp collection.

Sophie Ginsky the boys call Red,

She'll go far with her big brown eyes and her clever head.

And that was my mother!

Also, she had been secretary to the soccer coach, an office pretty much without laurels in our own time, but apparently the post for a young girl to hold in Jersey City during the First World War. So I thought, at any rate, when I turned the pages of her yearbook, and she pointed out to me her dark-haired beau, who had been captain of the team, and today, to quote Sophie, the biggest manufacturer of mustard in New York. And I could have married him instead of your father, she confided in me, and more than once. I used to wonder sometimes what that would have been like for my momma and me, invariably on the occasions when my father took us to dine out at the corner delicatessen. I look around the place and think, We would have manufactured all this mustard. I suppose she must have had thoughts like that herself.

He eats French fries, she says, and sinks into a kitchen chair to Weep Her Heart Out once and for all. He goes after school with Melvin Weiner and stuffs himself with French-fried potatoes. Jack, you tell him, I'm only his mother. Tell him what the end is going to be. Alex, she says passionately, looking to where I am edging out of the room, tateleh, it begins with diarrhea, but do you know how it ends? With a sensitive stomach like yours, do you know how it finally ends? Wearing a plastic bag to do your business in!

Who in the history of the world has been least able to deal with a woman's tears? My father. I am second. He says to me, You heard your mother. Don't eat French fries with Melvin Weiner after school.

Or ever, she pleads.

Or ever, my father says.

Or hamburgers out, she pleads.

Hamburgers, she says bitterly, just as she might say Hitler, where they can put anything in the world in that they want-and he eats them. Jack, make him promise before he gives himself a terrible tsura, and it's too late.

I promise! I scream. I promise! and race from the kitchen- to where? Where else.

I tear off my pants, furiously I grab that battered battering ram to freedom, my adolescent cock, even as my mother begins to call from the other side of the bathroom door. Now this time don't flush. Do you hear me, Alex? I have to see what's in that bowl!

Doctor, do you understand what I was up against? My wang was all I really had that I could call my own. You should have watched her at work during polio season! She should have gotten medals from the March of Dimes! Open your mouth. Why is your throat red? Do you have a headache you're not telling me about? You're not going to any baseball game, Alex, until I see you move your neck. Is your neck stiff? Then why are you moving it that way? You ate like you were nauseous, are you nauseous? Well, you ate like you were nauseous. I don't want you drinking from the drinking fountain in that playground. If you're thirsty wait until you're home. Your throat is sore, isn't it? I can tell how you're swallowing. I think maybe what you are going to do, Mr. Joe Di Maggie, is put that glove away and lie down. I am not going to allow you to go outside in this heat and run around, not with that sore throat, I'm not. I want to take your temperature. I don't like the sound of this throat business one bit. To be very frank, I am actually beside myself that you have been walking around all day with a sore throat and not telling your mother. Why did you keep this a secret? Alex, polio doesn't know from baseball games. It only knows from iron lungs and crippled forever! I don't want you running around, and that's final. Or eating hamburgers out. Or mayonnaise. Or chopped liver. Or tuna. Not everybody is careful the way your mother is about spoilage. You're used to a spotless house, you don't begin to know what goes on in restaurants. Do you know why your mother when we go to the Chink's will never sit facing the kitchen? Because I don't want to see what goes on back there. Alex, you must wash everything, is that clear? Everything! God only knows who touched it before you did.

Look, am I exaggerating to think it's practically miraculous that I'm ambulatory? The hysteria and the superstition! The watch- its and the becarefuls! You mustn't do this, you can't do that-hold it! don't! you're breaking an important law! What law? Whose law? They might as well have had plates in their lips and rings through their noses and painted themselves blue for all the human sense they made! Oh, and the milchiks and flaishiks besides, all those meshuggeneh rules and regulations on top of their own private craziness! It's a family joke that when I was a tiny child I turned from the window out of which I was watching a snowstorm, and hopefully asked, Momma, do we believe in winter? Do you get what I’m saying? I was raised by Hottentots and Zulus! I couldn't even contemplate drinking a glass of milk with my salami sandwich without giving serious offense to God Almighty. Imagine then what my conscience gave me for all that jerking off!

The guilt, the fears-the terror bred into my bones! What in their world was not charged with danger, dripping with germs, fraught with peril? Oh, where was the gusto, where was the boldness and courage? Who filled these parents of mine with such a fearful sense of life? My father, in his retirement now, has really only one subject into which he can sink his teeth, the New Jersey Turnpike. I wouldn't go on that thing if you paid me. You have to be out of your mind to travel on that thing- it's Murder Incorporated, it's a legalized way for people to go out and get themselves killed- Listen, you know what he says to me three times a week on the telephone-and I'm only counting when I pick it up, not the total number of rings I get between six and ten every night. Sell that car, will you? Will you do me a favor and sell that car so I can get a good night's sleep?

Why you have to have a car

in that city is beyond my comprehension. Why you want to pay for insurance and garage and upkeep, I don't even begin to understand. But then I don't understand yet why you even want to live by yourself over in that jungle.

What do you pay those robbers again for that two-by-four apartment? A penny over fifty dollars a month and you're out of your mind. Why you don't move back to North Jersey is a mystery to me-why you prefer the noise and the crime and the fumes-

And my mother, she just keeps whispering. Sophie whispers on! I go for dinner once a month, it is a struggle requiring all my guile and cunning and strength, but I have been able over all these years, and against imponderable odds, to hold it down to once a month: I ring the bell, she opens the door, the whispering promptly begins!

Don't ask what kind of day I had with him yesterday. So I don't. Alex, sotto voce still, when he has a day like that you don't know what a difference a call from you would make. I nod. And, Alex - and I'm nodding away, you knowit doesn't cost anything, and it may even get me through- next week is his birthday. That Mother's Day came and went without a card, plus my birthday, those things don't bother me. But he'll be sixty-six, Alex. That's not a baby, Alex-that's a landmark in a life. So you'll send a card. It wouldn't kill you.

Doctor, these people are incredible! These people are unbelievable! These two are the outstanding producers and packagers of guilt in our time! They render it from me like fat from a chicken! Call, Alex. Visit, Alex. Alex, keep us informed. Don't go away without telling us, please, not again. Last time you went away you didn't tell us, your father was ready to phone the police. You know how many times a day he called and got no answer? Take a guess, how many? Mother, I inform her, from between my teeth, if I'm dead they'll smell the body in seventy-two hours, I assure you! Don't talk like that! God forbid! she cries. Oh, and now she's got the beauty, the one guaranteed to do the job. Yet how could I expect otherwise? Can I ask the impossible of my own mother?

Alex, to pick up a phone is such a simple thing- how much longer will we be around to bother you anyway?

Doctor Spielvogel, this is my life, my only life, and I'm living it in the middle of a Jewish ioke! I am the son in the Jewish joke- only it aint no joke! Please, who crippled us like this? Who made us so morbid and hysterical and weak? Why, why are they screaming still, Watch out! Don't do it! Alex- no! and why, alone on my bed in New York, why am I still hopelessly beating my meat? Doctor, what do you call this sickness I have? Is this the Jewish suffering I used to hear so much about? Is this what has come down to me from the pogroms and the persecution? from the mockery and abuse bestowed by the goyim over these two thousand lovely years? Oh my secrets, my shame, my palpitations, my flushes, my sweats! The way I respond to the simple vicissitudes of human life! Doctor, I can't stand any more being frightened like this over nothing! Bless me with manhood! Make me brave! Make me strong! Make me whole! Enough being a nice Jewish boy, publicly pleasing my parents while privately pulling

my putz! Enough!

[... ... ...]