Ispirazione mistica/Capitolo 11

La Cabala classica

[modifica | modifica sorgente]

| Per approfondire, vedi TABELLA CABALA: tutte le voci su Wikipedia. |

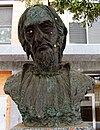

Moses de León

[modifica | modifica sorgente]| Per approfondire, vedi Introduzione allo Zohar e Zohar. |

Ora che abbiamo esaminato gli inizi della Cabala e il suo vocabolario di simbolismo mistico, entriamo nel periodo in cui matura la Cabala in Spagna. Gruppi di mistici che la pensavano allo stesso modo si riunirono per spronarsi a vicenda nelle loro pratiche di meditazione, per discutere le rivelazioni che avevano sperimentato, per spiegare ed espandere i miti e il simbolismo che stavano creando. Spesso si sottomettevano a uno di loro come al primo tra pari, loro maestro sul cammino spirituale. Un esempio importante è Moses de León e i suoi compagni nella Spagna del XIII secolo, che si presume siano gli autori dello Zohar, che divenne il testo centrale della Cabala.

Entro la metà del XVI secolo lo Zohar era diventato sacro quanto la Torah e il Talmud. Zohar (זוהר) significa splendore, luce brillante. È scritto sotto forma di un classico commentario mistico alla Torah e incorpora racconti fantasiosi sul rabbino Simeon bar Yohai, un famoso saggio del II secolo e mistico leggendario, e su un gruppo di rabbini che erano suoi discepoli. Le interazioni tra questi rabbini e le loro discussioni sui significati più profondi racchiusi nella Torah servono come voce narrativa degli insegnamenti presentati nello Zohar. Ciò che è più importante su Rabbi Simeon rappresentato nello Zohar è la sua grande conoscenza dei segreti della Torah e, in effetti, di tutti i segreti mistici, combinata con il suo permesso da parte di Dio di rivelarli.

Moses ben Shem Tov de León, passato alla storia come Moses de León, nacque ad Arévalo, in Spagna, nell'anno 1250. Fino al 1290 visse a Guadalajara, un centro di seguaci della Cabala. Successivamente viaggiò molto e infine si stabilì ad Ávila, dove morì nel 1305. De León, durante la sua vita, sostenne di essere solo uno scriba che copiava da un antico libro di saggezza che aveva ritrovato. Disse che l'autore del libro non era altro che il famoso saggio Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai stesso.

Era comunemente accettato durante la vita di de León e per secoli dopo, che il libro fosse stato scritto da Rabbi Simeon. Tuttavia ci fu sempre chi dubitava dell'autenticità della sua paternità. Nel 1305, Isaac, figlio di Samuel di Akko, un cabalista di grande profondità, raggiunse la Spagna dopo aver vagato per il mondo ebraico mediterraneo dal momento della caduta di Akko nel 1291. Aveva sentito parlare dello Zohar ed era venuto a Valladolid in cerca della verità sulla sua origine. Il diario di Isaac era noto allo storico Abraham Zacuto, che lo cita nel suo libro Sefer ha-yuhasin (Libro di Genealogia). A quanto pare, Isaac riuscì a incontrare de León, che accettò di mostrargli il manoscritto originale se Isaac lo avesse incontrato ad Ávila. I due si separarono e concordarono una data per incontrarsi a casa di de León ad Ávila.

Sfortunatamente, quando Isaac raggiunse Avila, Moses era morto. Isaac interrogò un altro studioso riguardo al manoscritto, il quale raccontò una conversazione con la vedova di Moses. Disse che non c'era mai stato un vecchio manoscritto da cui avesse copiato, ma che lo aveva scritto lui stesso solo per far soldi. Isaac registra le sue parole:

Isaac menziona che Moses era conosciuto come qualcuno che aveva contatto con il santo nome divino e che, sebbene non avesse avuto un antico manoscritto, si pensava comunemente che scrivesse sotto ispirazione e potere del santo nome, forse canalizzando il libro in uno stato di trance. Gli amici cabalisti più stretti di de León non avrebbero visto nulla di sbagliato in ciò che stava facendo per rafforzare gli insegnamenti in cui anche loro credevano. E in effetti, la pseudepigrafia (dove i testi religiosi sono attribuiti ad antiche personalità rispettate) era un modo comune di presentare insegnamenti innovativi e forse eretici, conferendo loro l'autorità e l'anonimato della tradizione. Quindi, nonostante la testimonianza della vedova di de León e un certo scetticismo sulla paternità di Simeon, nel corso dei secoli lo Zohar divenne ancora più venerato come testo sacro di Rabbi Simeon. Fu solo nel 1920, quando Gershom Scholem fece la ricerca più intensa e l'analisi linguistica e stilistica, confrontando lo Zohar con altri documenti scritti da de León, che il mondo accademico si convinse che Moses de León fosse l’autore del libro. Ricerche e analisi molto recenti confermano le conclusioni di Scholem ma suggeriscono che Moses de León non fosse l’unico autore dello Zohar; dimostra che i suoi colleghi cabalisti scrissero sezioni del libro con Moses de León al centro di quella che avrebbe potuto essere una sorta di fratellanza mistica, impegnata per un periodo di trenta o quaranta anni a mettere per iscritto la loro percezione della realtà spirituale.[2]

Non è noto se Moses de León avesse discepoli o se si trattasse di una fratellanza tra pari, ma la relazione e il modo di diffondere i concetti mistici da maestro a discepoli sono meravigliosamente descritti nello Zohar. L'atmosfera, gli scambi orali, il verso poetico e l'amore tra maestro e discepolo sono fedeli al tempo e al luogo. La maggior parte dei concetti mistici dello Zohar non erano nuovi, ma non furono mai resi così chiari e intensi, né così stimolanti. Gli ammiratori e molti commentatori dello Zohar nel corso dei secoli sottolineano come lo strato più profondo di saggezza contenuto nelle parole del libro vibri con una forza magnetica che trascina lo studente serio in un mondo al di là dei concetti.

De León era un mistico il cui studio persistente e amore per la Torah lo portarono nel reame dell'unione mistica attiva e causò una profonda rivoluzione nell'ebraismo che si riverberò attraverso i secoli fino ai giorni nostri. Per de León, lo Zohar è un mezzo per raggiungere un fine (unione mistica con Dio) e ispira a vivere la Torah e ad elevarsi al di sopra del livello della conoscenza intellettuale. In un altro dei suoi libri, Or zaru’a (Luce Seminata), de León scrive:[3]

I have seen some people called “wise.” But they have not awoken from their slumber; they just remain where they are... Indeed, they are far from searching for His glorious Reality. They have exchanged His Glory for the image of a bull eating grass (cf. Psalms 106:20)...

The ancient wise ones have said that there was once a man engaged in Mishnah and Talmud all his day according to his animal knowledge. When the time came for him to depart from the world, he was very old, and people said that he was a great wise man. But one person came along and said to him, “Do you know your self? All the limbs in your body, what are they for?” He said, “I do not know.” “Your little finger, what is it for?” He said, “I do not know.” “Do you know anything outside of you, why it is, how it is?” He began shouting at everyone, “I do not know my self! How can I know anything outside my self?” He went on, “All my days I have toiled in Torah until I was eighty years old. But in the final year I attained no more wisdom or essence than I attained in those first years when I began studying.” The people asked, “Then what did you toil over all these years?” He said, “What I learned in the beginning.” They said, “This wise man is nothing but an animal without any knowledge. He did not know the purpose of all his work; just like an animal carrying straw on its back, not knowing whether it is sifted grain or straw!”... See how my eyes shine, for I have tasted a bit of this honey! O House of Jacob! Come, let us walk in the light of YHWH![4]

“This wise man is nothing but an animal without knowledge”, Moses de León si riferisce ai rabbini e agli studiosi che possono citare a memoria qualsiasi versetto della Torah proprio come fanno i sacerdoti e i saggi di tutte le religioni dalle loro scritture – coloro per i quali Dio è un libro da studiare e adorare. Per de León e altri cabalisti, la Torah era l'afflato di Dio. Lo Zohar fu il tentativo fatto da de León di far rivivere “the eyes that shine because they have tasted the honey of Torah”. Ci furono “generations of devotees who sought to make its poetry transparent, to see beyond the imagery into the ‘true’ religious meaning of the text,... to find in each word or phrase previously unseen layers of sacred meaning”.[5]

Un tema importante dello Zohar è che la Torah come libro indica la Torah come una presenza divina vivente: “Torah in the Zohar is not conceived as a text, as an object, or as material, but as a living divine presence, engaged in a mutual relationship with the person who studies her”.[6]

In una narrazione sul significato della Torah nello Zohar, Rabbi Simeon dice quanto segue:

Alas for the man who regards the Torah as a book of mere tales and everyday matters! If that were so, we, even we could compose a torah dealing with everyday affairs, and of even greater excellence. Nay, even the princes of the world possess books of greater worth which we could use as a model for composing some such torah. The Torah, however, contains in all its words supernal truths and sublime mysteries. Observe the perfect balancing of the upper and the lower worlds. Israel here below is balanced by the angels on high, of whom it says: “who makest thy angels into winds” (Psalms 104:4). For the angels in descending on earth put on themselves earthly garments, as otherwise they could not stay in this world, nor could the world endure them. Now, if thus it is with the angels, how much more so must it be with the Torah – the Torah that created them, that created all the worlds and is the means by which these are sustained.

Thus had the Torah not clothed herself in garments of this world, the world could not endure it. The stories of the Torah are thus only her outer garments, and whoever looks upon that garment as being the Torah itself, woe to that man – such a one will have no portion in the next world. David thus said: “Open thou mine eyes, that I may behold wondrous things out of thy law” (Psalms 119:18), to wit, the things that are beneath the garment.

Observe this. The garments worn by a man are the most visible part of him, and senseless people looking at the man do not seem to see more in him than the garments. But in truth the pride of the garments is the body of the man, and the pride of the body is the soul. Similarly the Torah has a body made up of the precepts of the Torah, called gufei torah [bodies of the Torah, i.e., main principles of the Torah], and that body is enveloped in garments made up of worldly narrations. The senseless people only see the garment, the mere narrations; those who are somewhat wiser penetrate as far as the body.[7]

La creazione avvenne attraverso le parole della Torah, dichiara Rabbi Simeon:

See now, it was by means of the Torah that the Holy One created the world. That has already been derived from the verse, “Then I was near him as an artisan, and I was daily all his delight” (Proverbs 8:30). He looked at the Torah once, twice, thrice, and a fourth time. He uttered the words composing her and then operated through her...

Hence the account of the creation commences with the four words Bereshit bara Elohim et [“In-the- beginning created God the”], before mentioning “the heavens,” thus signifying the four times which the Holy One, blessed be He, looked into the Torah before He performed His work.[8]

In altro punto, Rabbi Simeon riassume il potere della Torah come guida ultima per la vita:

Observe how powerful is the might of the Torah, and how it surpasses any other force. For whoso occupies himself in the study of the Torah has no fear of the powers above or below, nor of any evil happenings of the world. For such a man cleaves to the tree of life, and derives knowledge from it day by day, since it is the Torah that teaches man to walk in the true path.[9]

Per de León e i suoi compagni, il testo della Torah narrato e interpretato nello Zohar è una forza creativa dinamica, il santo nome o espressione. E gli oltre trecento racconti e riflessioni contenuti in una ventina di volumi dello Zohar sono un mezzo per aiutare lo studente che si avvia verso il contatto con la Torah “viva e divina”. Lo studio della Torah per questi mistici non era solo un dovere; era il loro supremo piacere. E le loro interpretazioni mistiche e simboliche fornivano una motivazione soprannaturale per l'osservanza dei comandamenti.

Nello Zohar, si dice che Rabbi Eleazar abbia detto: "Pertanto studiare la Torah è come studiare il santo nome, come abbiamo detto, che la Torah è tutta un santo nome superno".[10]

Attraverso le numerose storie di un gruppo di discepoli riuniti attorno al loro maestro in un giardino, in un boschetto o attorno a un fuoco a mezzanotte, in una locanda, o conversando mentre camminano tranquillamente da un villaggio all'altro, lo Zohar prende le leggi e narrazioni della Torah e le interpreta sia a livello concettuale che simbolico, leggendo in esse verità e principi mistici, investendole di un potere esponenziale. Vede la Torah come la potenza di Dio proiettata nella creazione ed esplora gli elementi microcosmici che compongono quella potenza e il modo in cui si dividono in varie sfere (le dieci sefirot – il dispiegarsi della creazione). Rabbi Simeon e i suoi discepoli trascorrono molte ore a scandagliare i significati più profondi dei passi della Torah, come la Torah sostiene il mondo, i vari livelli dell'anima, la struttura simbolica del corpo umano e molti altri argomenti.

Maestro e discepolo seduti o camminando insieme in questo mondo mondano e discutendo dei reami divini e delle questioni dello spirito, era la modalità comune di insegnamento e trasmissione.[11] Arthur Green in A Guide to the Zohar scrive:

These tales of Rabbi Simeon and his disciples wandering about Galilee a thousand years before the Zohar was written are clearly works of fiction. But to say so is by no means to deny the possibility that a very real mystical brotherhood underlies the Zohar and shapes its spiritual character. Anyone who reads the Zohar over an extended period will come to see that the interface among companions and the close relationship between the tales of their wanderings and the homilies those wanderings occasion are not the result of fictional imagination alone. Whoever wrote the work knew very well how fellow students respond to companionship and support and are inspired by one another’s glowing renditions of a text. He (or they) has felt the warm glow of a master’s praise and the shame of being shown up by a stranger in the face of one’s peers.

Leaving aside for now the question of who actually penned the words, we can say that the Zohar reflects the experience of a kabbalistic circle. It is one of a series of such circles of Jewish mystics, stretching back in time to Qumran, Jerusalem, Provençe, and Gerona, and forward in history to Safed, Padua, Miedzybozh, Bratslav, and again to Jerusalem. A small circle of initiates gathered about a master is the way Kabbalah has always happened, and the Zohar is no exception. In fact, the collective experience of this group around Rabbi Simeon as “recorded” in the Zohar forms the paradigm for all later Jewish mystical circles.[12]

Ma per quanto lo Zohar insegni la Torah a livello simbolico, attraverso le narrazioni dei suoi personaggi, la sua essenza è la storia del maestro e dei discepoli riuniti attorno a lui. La storia di Rabbi Simeon e del suo circolo è un sottile velo sopra la storia di Moses de León e del suo circolo cabalista. E il peregrinare dei santi uomini che studiano il significato profondo della Torah è di per sé una metafora dello spirito divino, la Shekhinah, che vaga in esilio nel mondo e sceglie di rivelarsi attraverso i santi che cercano di compiere la volontà divina in ogni aspetto della loro vita.

Con questo in mente, metteremo da parte la ricchezza degli insegnamenti mistici e delle interpretazioni del processo di creazione contenuti nello Zohar, e osserveremo più da vicino ciò che rivela sul maestro spirituale e sulla sua profonda relazione coi suoi discepoli.

È degna di nota la grande riverenza con cui Simeon bar Yohai viene trattato dai suoi discepoli. Lo elevano al livello più alto, a volte addirittura equiparandolo a Dio. Egli evoca grande gratitudine per la grazia e la luce che dona loro. “Felice è la generazione in cui vive Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai!”[13]

"The figure of Simeon bar Yohai became a paradigm for medieval kabbalists. Not only did he know where to go in the ascent to heaven, he also possessed the great redemptive capacity to atone for the sins of others".[14] Non c’è da meravigliarsi che molti dei cabalisti successivi affermassero di essere la sua reincarnazione.

Ecco alcuni commenti dei suoi discepoli su di lui. In questo primo resoconto, Rabbi Simeon viene chiamato “la lampada sacra” (the sacred lamp). Viene anche paragonato a Mosè, venerato come il più grande dei profeti, e si presume che sia la reincarnazione di Mosè. Lo Zohar dice che in questa generazione, la santità di Rabbi Simeon porta i miracoli dello spirito santo nel mondo:

Rabbi Jose said: Let us take these things [the mysteries of the scriptures] up to the sacred lamp, for he prepares sweet dishes [reveals spiritual mysteries], like those of the holy Ancient One [Atika Kadisha], the mystery of all mysteries; he prepares dishes that do not need salt from another. Furthermore, we can eat and drink our fill from all the delights of the world, and still have some to spare. He fulfills the verse “So he set it before them, and they ate, and had some to spare, according to the word of the Lord” (2 Kings 4:44)...

Rabbi Isaac said: What you say is true, for one day I was walking along with him, and he opened his mouth to speak Torah, and I saw a pillar of cloud stretching down from heaven to earth, and a light shone in the middle of the pillar. I was greatly afraid and I said: Happy is the man for whom such things can happen in this world. What is written concerning Moses? “And when all the people saw the pillar of cloud stand at the door of the tent, all the people arose and worshiped, every man at his tent door” (Exodus 33:10). This was most fitting for Moses, the faithful prophet, supreme over all the world’s prophets, and for that generation, who received the Torah at Mount Sinai and witnessed so many miracles and examples of power in Egypt and at the Red Sea. But now, in this generation, it is because of the supreme merit of Rabbi Simeon that wonders are revealed at his hands.[15]

Viene descritta un'esperienza spirituale condivisa di Rabbi Simeon e di suo figlio, Rabbi Eleazar:

Rabbi Simeon came and kissed him on the head. He said to him: Stand where you are, my son, for your moment has now come.

Rabbi Simeon sat down, and Rabbi Eleazar, his son, stood and expounded wisdom’s mysteries, and his face shone like the sun, and his words spread abroad and moved in the firmament.

They sat for two days, and did not eat or drink, not knowing whether it was day or night. When they left they realized that they had not eaten anything for two days.[16]

Rabbi Simeon poi esclama a suo figlio che se abbiamo avuto una simile esperienza dopo così poco tempo, immagina cosa visse Mosè, che trascorse quaranta giorni con il Signore sul Monte Sinai!

Dopo aver sentito parlare di questo evento, Rabbi Gamaliel, il capo dell'accademia, dice che Rabbi Simeon è così grande che persino Dio gli obbedisce. Non deve digiunare o compiere altre austerità per influenzare Dio. È un tema comune nel lodare i santi in tutte le tradizioni mistiche dire che sono più grandi di Dio:

Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai is a lion, and Rabbi Eleazar, his son, is a lion. But Rabbi Simeon is not like other lions. Of him it is written, “The lion has roared; who will not fear?” (Amos 3:8). And since the worlds above trembled before him, how much more should we? He is a man who has never had to ordain a fast for something that he really desired. But he makes a decision, and the Holy One, blessed be He, supports it. The Holy One, blessed be He, makes a decision, and he annuls it. . . . The Holy One, blessed be He, is the ruler over man, but who rules over the Holy One, blessed be He? The righteous, for He makes a decision, and the righteous annuls it.[17]

In un altro resoconto, Rabbi Hiya, un membro della compagnia di Rabbi Simeon, dice:

This is Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai, who shatters all things. Who can stand before him? This is Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai, whose voice, when he opens his mouth and begins to study Torah, is heeded by all the thrones, all the firmaments, and all the chariots, and all of these, who praise their master, neither open nor close [their mouths] – all of them are silent, until in all the firmaments, above and below, no sound is heard. When Rabbi Simeon completes his study of the Torah, who has seen the songs, who has seen the joy of those who praise their master? Who has seen the voices that travel through all the firmaments? They all come on account of Rabbi Simeon, and they bow and prostrate themselves before their master, exuding the odors of the spices of Eden as far as the Ancient of Days [Atika Kadisha] and all this on account of Rabbi Simeon.[18]

Prima della sua morte, Rabbi Simeon rivela altri misteri ai suoi discepoli e li avverte su chi insegnerà loro quando se ne sarà andato:

Now is a propitious hour, and I am seeking to enter the world-to- come without shame. There are sacred matters that have not been revealed up till now and that I wish to reveal in the presence of the Shekhinah, so that it should not be said that I departed from the world with my work incomplete. Until now they have been concealed in my heart, so that I might enter the world-to- come with them. And so I give you your duties: Rabbi Abba will write them down, Rabbi Eleazar, my son, will explain them, and the other companions will meditate silently upon them.[19]

Rabbi Abba aveva descritto la relazione di Rabbi Simeone con i suoi discepoli prima della sua morte:

It is taught that from that day forward the companions did not leave Rabbi Simeon’s house, and that when Rabbi Simeon was revealing secrets, only they were present with him. And Rabbi Simeon used to say of them: We seven are the eyes of the Lord, as it is written, “these seven, the eyes of the Lord” (Zechariah 4:10). Of us is this said.

Rabbi Abba said: We are six lamps that derive their light from the seventh [like the menorah lampstand, whose six lamps are lit by the “chief ” candle]. You are the seventh over all, for the six cannot survive without the seventh. Everything depends on the seventh.

Rabbi Judah called him “Sabbath,” because the [other] six [days] receive blessing from it, for it is written “Sabbath to the Lord” and it is also written “Holy to the Lord.” Just as the Sabbath is holy to the Lord, so Rabbi Simeon, the Sabbath, is holy to the Lord.[20]

Successivamente Rabbi Hiya fu chiamato “la luce della lampada della Torah” (the light of the lamp of the Torah), intendendo la luce accesa dal suo maestro. E più tardi lo Zohar racconta la morte di Rabbi Simeon in termini di apparizione di luce e fuoco, in modo simile al modo in cui la Torah descrive la rivelazione divina che Mosè sperimentò nel roveto ardente:

Rabbi Abba said: The holy light [Rabbi Simeon] had not finished saying “life,” when his words were hushed. I was writing as if there were more to write, but I heard nothing. And I did not raise my head, for the light was strong, and I could not look at it. Then I became afraid. . . . All that day the fire did not leave the house, and no one could get near it. They were unable, because the light and the fire surrounded it the whole day. I threw myself upon the ground and groaned. When the fire had gone I saw that the holy light, the holy of holies, had departed from the world. He was lying on his right side, wrapped in his cloak, and his face was laughing. Rabbi Eleazar, his son, rose, took his hands and kissed them, and I licked the dust beneath his feet. The companions wanted to mourn but they could not speak. The companions began to weep, and Rabbi Eleazar, his son, fell three times, and he could not open his mouth...

Rabbi Hiya got to his feet, and said: Up till now the holy light has taken care of us. Now we can do nothing but attend to his honor.

Rabbi Eleazar and Rabbi Abba rose, and put him in a litter. Who has ever seen disarray like that of the companions? The whole house exuded perfume.[21]

Lo Zohar racconta poeticamente l'angoscia dei discepoli per la perdita del loro maestro. Era la fonte della loro conoscenza dei misteri celesti, della loro profonda esperienza mistica.

It is taught that Rabbi Jose said: From the day that Rabbi Simeon left the cave, matters were not hidden from the companions, and the celestial mysteries were radiated and revealed among them as if they had been promulgated at that very moment on Mount Sinai. When he died it was as is written “the fountains of the deep and the windows of heaven were stopped” (Genesis 8:2), and the companions experienced things that they did not understand.[22]

La riverenza e l'amore di Rabbi Judah per Rabbi Simeon sono espressi magnificamente in un simbolico grido di desiderio:

When he awoke [from his dream], he said: Truly, since Rabbi Simeon died, wisdom has departed from the world. Alas for the generation that has lost the precious stone, from which the upper and the lower regions looked down, and from which they gained their support![23]

Un altro elemento interessante nel concetto di maestro spirituale nello Zohar, che è quasi un sottotesto ricorrente, è che il vero uomo santo si nasconde alla vista ed è spesso sconosciuto a coloro che lo circondano. Arthur Green scrive:

Il mulattiere appare nello Zohar come metafora del maestro spirituale, addirittura del messia. La predizione biblica della venuta del Messia lo immagina cavalcare un mulo – colui “che verrà umile, cavalcando un asino” (Zaccaria 9:9). L'uso di questa metafora da parte dello Zohar indica l'umiltà del maestro spirituale, come anche la natura simile a un mulo del discepolo che deve guidare, che è governato dalla sua mente ostinata.

Questa parabola inizia quando Rabbi Eleazar e Rabbi Abba intraprendono un lungo viaggio insieme. Lungo il percorso entrano in discussione su alcuni punti salienti delle Scritture. Il mulattiere, che guidava i muli dietro di loro, si unisce alla discussione e lentamente si rendono conto che "ha una saggezza che non conosciamo". Nel corso del racconto i rabbini gli dicono:

You have not told us your name nor the place where you live.

He replied: The place where I live is fine and exalted for me. It is a tower, flying in the air, great and beautiful. And these are they who dwell in the tower: the Holy One, blessed be He, and a poor man. This is where I live. But I am exiled from there, and I am a mule‑driver. [I am exiled from the higher spiritual regions and must live in this world, this earth plane, as a mule-driver.]

Rabbi Abba and Rabbi Eleazar looked at him, and his words pleased them. They were as sweet as manna and honey.

They said: If you tell us the name of your father, we shall kiss the dust of your feet.

Why? he asked. It is not my wont to use the Torah in order to exalt myself. But my father used to live in the great sea, and he was a fish [nuna][24] that used to circumnavigate the great sea from end to end. [He crossed the ocean of phenomena.] He was so great, ancient, and honorable that he used to swallow all the other fish in the sea, and spew them out again, live and healthy, and full of all the goodness in the world. He was so strong that he could cross the sea in a single second, and he produced me like an arrow from a mighty warrior’s hand. He hid me in the place that I described to you, and then he returned to his place and concealed himself in the sea.

Rabbi Eleazar considered his words, and said: You are really the son of the sacred lamp, you are really the son of Rav Hamnuna Sava, you are really the son of the light of the Torah, and yet you drive mules behind us?

They both wept together, and kissed him, and continued their journey.[25]

Lo Zohar racconta un'altra storia, forse la rivisitazione di un vecchio racconto popolare, di un uomo che piange perché ha dato sua figlia in sposa a un uomo che non sa nulla della Torah; non conosce nemmeno la benedizione dopo i pasti. All'inizio il padre pensò che lo sposo fosse un ardente studioso della Torah perché saltò nella sinagoga da un tetto vicino per ascoltare le preghiere. Ma poi (dopo il matrimonio) il padre si rende conto che il ragazzo non sa assolutamente nulla. Tutto questo viene rivelato dal padre a due discepoli di Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai. E mentre la discussione va avanti, ancora una volta – come all'inizio del racconto – il giovane sposo irrompe nel gruppo e spiega perché ha nascosto a tutti la sua vera identità, e che in realtà è un grande studioso della Torah e amante di Dio. E c'è grande gioia in casa!

Questa storia risuona di temi inculcati nel misticismo ebraico, principalmente quello della necessità di nascondere ciò che è grande. Mostra il modo unico in cui i cabalisti giocano con i loro discepoli e lettori presentando un qualcosa che a prima vista appare come una cosa e, se guardato di nuovo, è compreso come qualcosa di molto diverso: il nascosto e il rivelato e la loro interdipendenza. Ciò è legato a una convinzione spirituale profondamente radicata nell'ebraismo secondo cui il potere divino di Dio insegna attraverso tutte le cose e le persone, e quindi non si dovrebbe mai ignorare ciò che potrebbe sembrare insignificante o privo di importanza spirituale a causa dei suoi "vestimenti" o del suo aspetto.

Gli insegnamenti cabalistici e lo Zohar in particolare presentano costantemente persone che affermano di non sapere nulla ma poi viene rivelata la loro vera grandezza spirituale. Nel pensiero cabalistico si ritiene che gli insegnamenti esoterici siano nascosti ovunque e possano provenire da chiunque. I segreti nascosti della vita, gli strati di illusione che circondano la percezione già limitata di un uomo, sono evidenziati in racconti simili nello Zohar. Come il vero significato della Torah è nascosto, rivelato attraverso lo Zohar, così la verità del maestro è nascosta e rivelata nelle narrazioni dello Zohar. Inoltre, un tema ricorrente nello Zohar è che un uomo di grandezza spirituale dovrebbe nascondersi nell'oscurità, che è forse ciò che stava facendo lo stesso Moses de León.

Abraham Abulafia

[modifica | modifica sorgente]| Per approfondire, vedi Abulafia e i segreti della Torah . |

Abraham (Abramo) Abulafia era un cabalista spagnolo del XIII secolo, significativo perché il suo metodo dettagliato per praticare la Cabala offriva la speranza di un'esperienza estatica di unione con il divino, in cui "i confini che separano il sé e Dio vengono superati".[26] Il sistema di Abulafia emerse come alternativa all'approccio teosofico e intellettuale della maggior parte dei cabalisti del suo tempo, preoccupati di meditare sul simbolismo delle sefirot che compongono i reami divini e non su un percorso pratico di devekut, un intimo unirsi a Dio attraverso l’ascesa interiore. Abulafia chiamò il suo insegnamento “cabala profetica” (kabbalah nevu’it), poiché era concepito per indurre uno stato di illuminazione interiore. Gli studiosi moderni l'hanno chiamata “Cabala estatica”.

Abulafia nacque nel 1240 a Saragozza, in Aragona, che al momento della sua nascita era sotto il dominio musulmano. Morì intorno al 1291. Molto presto nella vita fu portato dai suoi genitori a Tudela, in Navarra, che ospitava molti studiosi e mistici ebrei. Lì il padre di Abraham lo istruì nella Bibbia e nel Talmud. Quando aveva diciotto anni morì il suo anziano padre e due anni dopo Abraham iniziò una vita di lunghi viaggi. Dapprima si recò in Palestina per cercare le dieci tribù perdute che, secondo la leggenda, si trovavano presso il mitologico fiume Sambatyon, menzionato in molti antichi testi ebraici.[27] Ma il suo viaggio fu interrotto a causa dei combattimenti e del caos in Terra Santa dopo le ultime crociate.

Abulafia ritornò in Europa dove si sposò, e visse in Italia. A Capua studiò la Guida dei perplessi di Maimonide con Rabbi Hillel di Verona.[28] Nonostante il suo intenso impegno nel percorso dell'esperienza mistica, Abulafia fu profondamente influenzato da Maimonide e dall'approccio filosofico corrente a quel tempo. Adottò il concetto dato da Maimonide dell’Intelletto Attivo che emana da Dio e dirige la creazione fisica. Lo associava alla proiezione del potere divino, che è presente in ogni cosa. L'Intelletto Attivo può toccare l'intelletto umano (il potenziale spirituale umano) che è stato realizzato attraverso la meditazione. L'essere umano può così ricevere l'influsso divino, la traboccante coscienza spirituale divina che irradia da Dio. Abulafia talvolta chiama l'Intelletto Attivo dibur kadmon, il discorso o parola primordiale. La Bibbia chiama l'intelletto o la coscienza umana “l’immagine di Dio”, nella quale l’uomo è stato creato.[29]

Scholem sottolinea che per Abulafia esiste "a stream of cosmic life – personified for him in the intellectus agens (active intellect) of the philosophers, which runs through the whole of creation. There is a dam which keeps the soul confined within the natural and normal borders of human existence and protects it against the flood of the divine stream, which flows beneath it or all around it; the same dam, however, also prevents the soul from taking cognizance of the Divine".[30] Attraverso le pratiche meditative da lui sviluppate, Abulafia cercò di aprirsi interiormente per ricevere questa corrente divina.

Quando Abulafia tornò in Spagna dall'Italia, studiò la Cabala, in particolare il primo testo del Sefer yetsirah (Libro della Formazione) che presenta la creazione come avvenuta attraverso le lettere dell'alfabeto ebraico, i numeri, i pianeti e le dimensioni spaziali. Si immerse nei commentari al Sefer yetsirah scritti da Eleazar di Worms, il famoso hasid ashkenazita che insegnò varie meditazioni sui nomi di Dio. Sebbene i metodi che Abulafia sviluppò in seguito fossero unici, riconobbe di aver adottato elementi da Eleazar di Worms. A sua volta, Eleazar sostenne che Abramo già conosceva il sistema di combinazione delle lettere e diceva che erano segreti tramandati oralmente di generazione in generazione, fino a raggiungere i mistici nel periodo medievale.

Si racconta che nel 1270 Abulafia ebbe una rivelazione che influenzò il corso della sua vita. Alcuni studiosi scrivono che Dio apparve ad Abulafia e gli comandò di incontrare il Papa; altri dicono che una voce interiore gli parlò. Comunque sia, sulla base di una rivelazione, nel 1280 si recò a Roma per convertire papa Niccolò III all'ebraismo. Il Papa venne a conoscenza di ciò e diede ordine di bruciare sul rogo Abulafia non appena fosse arrivato. Fuori dalla città di Roma fu eretto un palo. Fortunatamente per Abulafia, la notte prima del suo arrivo il Papa ebbe un ictus e morì. Tuttavia, Abulafia fu catturato e gettato brevemente in prigione.

Di lui si sentì poi parlare in Sicilia nel 1281, dove affermò di essere il messia. Ormai aveva raccolto in Sicilia una cerchia di seguaci “che si muovevano al suo comando”. Il suo comportamento era bizzarro e i suoi insegnamenti sfidavano fortemente alcune delle credenze accettate nell'ebraismo tradizionale, anche tra i cabalisti. Ai suoi tempi era considerato un anticonformista, forsanche una persona pazza e pericolosa, poiché si autoproclamava profeta e messia. Di conseguenza fu gravemente attaccato dalla comunità ebraica ortodossa e fu costretto all'esilio sull'isola di Comino vicino alla Sicilia. Abulafia morì probabilmente intorno al 1291, non essendoci alcuna indicazione di sue attività o scritti successivi a quella data.

Abulafia iniziò a scrivere nel 1271 e produsse una cinquantina di testi. Sebbene fosse uno degli scrittori più prolifici del periodo medievale sulla Cabala, solo nel ventesimo secolo si ritrovarono molti dei suoi manoscritti. Tali libri includevano la sua interpretazione dei classici testi ebraici dell'antichità e resoconti delle sue esperienze spirituali. E, cosa più importante, molti dei suoi libri offrivano descrizioni dettagliate di complesse pratiche di meditazione basate sulla combinazione di lettere insieme ad altri esercizi, che divennero la base della Cabala estatica.

Sebbene ci sia molto poco scritto in italiano sulla relazione di Abulafia con i suoi seguaci, sembra che questi volessero qualcosa di più di una comprensione accademica di Dio. Abulafia offriva un percorso mistico non insegnato da altri cabalisti dell'epoca, a coloro che avevano il coraggio e la capacità di comprendere, memorizzare e mettere in pratica le sue tecniche. Inoltre, il suo messaggio offriva un viaggio impegnativo che, fino ad Abulafia, era appartenuto solo a quegli uomini di cui si parlava nella Torah e nel Talmud dei secoli passati. Il suo percorso richiedeva dedizione e disciplina di prim'ordine. Quanto segue dimostra la dedizione richiesta ai suoi studenti:

Sebbene Abulafia sia stato descritto come un asceta da alcuni studiosi, Moshe Idel, il più rinomato esperto contemporaneo di Abulafia, sottolinea che non era così estremo come lo furono alcuni dei suoi discepoli, né come le successive generazioni di cabalisti che combinarono le tecniche di Abulafia con le austerità influenzate dai sufi. Piuttosto, Abulafia credeva che rafforzando il proprio aspetto spirituale (intelletto) piuttosto che sopprimendo corpo, sensi o mente (immaginazione), sarebbe stato possibile raggiungere lo stato di profezia o addirittura l'unione mistica. Idel scrive: "As Abulafia understood man’s inner struggle as taking place between the intellect (spirit) and the imagination (mind), one cannot find in his writings extreme ascetic instructions... His approach is rather that, in order to attain ‘prophecy,’ one must act in the direction of strengthening the intellect rather than that of suppressing the body, the soul, or the imagination".[32] Questo è ben diverso da un percorso di estreme austerità.

Protendendosi verso il nome di Dio “astratto” e ineffabile, Abulafia concentrò le sue pratiche di meditazione su combinazioni e permutazioni dei nomi di Dio scritti o parlati, che secondo lui lo avrebbero portato in contatto con quella realtà impercettibile che è il vero nome astratto, così attirando l'influsso divino e attualizzando il suo intelletto. Come spiega Scholem, “Abulafia believes that whoever succeeds in making this great name of God, the least concrete and perceptible thing in the world, the object of his meditation, is on the way to true mystical ecstasy”.[33]

La sua tecnica di fusione nel “senzanome” o nella “parola” avveniva attraverso un complesso processo di combinazione di lettere, vocali e parole dell’alfabeto ebraico a livello scritto, poi a livello verbale (cantando le lettere) e infine a livello mentale attraverso la concentrazione. Alcune delle tecniche erano condivise con i cabalisti precedenti e con gli Hasidei Ashkenaz, ma una che Abulafia sembrava aver sviluppato lui stesso era tseruf, la pratica della combinazione di lettere. Letteralmente, tseruf significa fusione o immissione, nonché separazione del vero dal falso, del reale dall'irreale.

Inoltre prescriveva un metodo fisso di respirazione e di movimenti della testa e delle mani in accordo con le lettere vocalizzate (cfr. immagine supra). È probabile che Abulafia abbia incorporato elementi dei sistemi yogici del prāṇāyāma e delle asana nelle sue tecniche di respirazione e nelle posture del corpo. Scholem commenta che alcuni passaggi del suo libro Or ha-sekhel (Luce della mente) sembrano versioni giudaizzate di un manuale di yoga. Il fatto che Abulafia viaggiasse molto gli avrebbe dato l'opportunità di incontrare yogi e adepti di diversi percorsi spirituali.

Attraverso le sue pratiche, cercava di liberare l'anima dai “sigilli” e dai “nodi” che la legavano al mondo fisico e che la mantenevano in uno stato di separazione da Dio. Questi sigilli e nodi erano il modo in cui descriveva gli ostacoli, le inclinazioni inferiori e malvagie che impediscono all’Intelletto Attivo di fluire nella coscienza di una persona e di attualizzare il suo potenziale spirituale. Abulafia sosteneva che le lettere e le parole stesse non hanno potere da sole, ma quando vengono assorbite dal respiro e dall'intelletto spirituale dell'individuo diventano forze dinamiche con forme proprie che le trasformano in poteri, e le lettere trasformano così la persona che medita.

Abulafia e i suoi discepoli sperimentarono sia la luce interiore che il suono durante la loro meditazione. Ecco il resoconto di uno dei suoi discepoli riguardo all'esperienza della luce interiore:

Abulafia scrisse dei devoti che ascendono dal linguaggio umano esteriore al linguaggio interiore e si fondono nel linguaggio divino, il dibur kadmon:

Abulafia scrisse anche che la combinazione di lettere e nomi crea una sorta di musica interna nel meditatore. Le melodie vibrano interiormente e portano gioia al cuore di chi medita:[36]

I will now explain to you how the method of tseruf proceeds. You must realize that letter combination acts in a manner similar to listening with the ears. The ear hears sounds and the sounds merge, according to the form of the melody or the pronunciation. I will offer you an illustration. A violin and a harp join in playing and the ear hears, with sensations of love, variations in their harmonious playing. The strings touched with the right hand or the left hand vibrate, and the experience is sweet to the ears, and from the ears the sound travels to the heart and from the heart to the spleen [the seat of emotion]. The joy is renewed through the pleasure of the changing melodies, and it is impossible to renew it except through the process of combinations of sounds.

The combination of letters proceeds similarly. One touches the first string, that is, analogically, the first letter, and the right hand passes to the others, to second, third, fourth, or fifth strings, and from the fifth it proceeds to the others. In this process of permutations new melodies emerge and vibrate to the ears, and then touch the heart. This is how the technique of letter combination operates. . . . And the secrets which are disclosed in the vibrations rejoice the heart, for the heart then knows its God and experiences additional delight. This is alluded to in the verse (Psalms 19:8): “The Torah of the Lord is perfect, reviving the soul.” When it is perfect, it restores the soul.[37]

Abulafia fornisce istruzioni dettagliate per le sue tecniche di meditazione nel suo libro Hayei ha-olam ha-ba (La vita del mondo a venire). Include suggerimenti su come prepararsi per un periodo di meditazione, descrive la tecnica e guida il suo discepolo su cosa aspettarsi mentre sperimenta l’“afflusso intellettuale”. È interessante notare che, invece di spogliarsi del pensiero ed elevarsi al di sopra del processo meditativo, come insegnato in molti altri sistemi, egli aumenta intensamente il flusso del pensiero nella sua mente, forse rendendola iperattiva e perdendo il controllo, come un modo per elevarsene al di sopra. Abbiamo incluso questa selezione nella sua interezza perché copre tutti gli aspetti della pratica meditativa da lui insegnata:

Make yourself ready to meet your God, O Israel. Get ready to turn your heart to God alone, cleanse your body, and choose a special place where none will hear you, and remain altogether by yourself in isolation. Sit in one place in a room or in the attic, but do not disclose your secret to anybody. If you can do this in the day time in your own home, do even if only a little. But it is best to do it at night. Be careful to withdraw your thoughts from all the vanities of the world when you are preparing yourself to speak to your Creator, and you want Him to reveal to you His mighty deeds.

Robe yourself in your tallit [prayer shawl] and put the tefillin [phylacteries] on your head and hand; so that you may feel awed before the Shekhinah [divine immanence] that is with you at that time, cleanse your garments. If you can, let your garments all be white, for this is a very great aid to experiencing the fear and love for God. If you are doing this at night, kindle many lights so that your eyes will see brightly.

Then take in hand pen and ink and a writing board, and this will be your witness that you have come to serve your God in joy and with gladness of heart. Begin to combine letters, a few or many, reverse them and roll them around rapidly until your heart feels warm. Take note of the permutations, and of what emerges in the process. When your heart feels very warm at this process of combinations and you have understood many new subjects that you had not known through tradition or through your own reason, when you are receptive to the divine influence, and the divine influence has touched you and stirred you to perceptions one after another, get your purified thoughts ready to envision God, praised be He, and His supreme angels. Envision them in your heart as though they were people standing or sitting about you, and you are among them like a messenger whom the king and his ministers wish to send on a mission and he is ready to hear about his mission from the king or his ministers.

After envisioning all this, prepare your mind and heart to understand mentally the many subjects that the letters conjured up in you, concentrate on all of them, in all their aspects, like a person who is told a parable or a riddle or a dream or as one who ponders a book of wisdom in a subject so profound as to elude his comprehension which will make you receptive to seek any plausible interpretation possible.

All this will happen to you after you will have dropped the writing tablet from your hand and the quill from your finger or they will have fallen away by themselves, because of the intensity of your thoughts. And be aware that the stronger the intellectual influx will become in you, your outer and inner organs will weaken and your whole body will be agitated with a mighty agitation to a point where you will think you are going to die at that time, for your soul will separate from your body out of great joy in having comprehended what you have comprehended. You will choose death over life, knowing that this death is for the body alone, and that as a result of it your soul will enjoy eternal life.

Then you will know that you have attained the distinction of being a recipient of the divine influx, and if you will then wish to honor the glorious Name, to serve Him with the life of body and soul, cover your face and be afraid to look at God, as Moses was told at the burning bush (Exodus 3:5): “Do not draw near, remove the shoes from your feet, for the ground on which you stand is holy.”

Then return to your bodily needs, leave that place, eat and drink a little, breathe in fragrant odors, and restore your spirit until another time and be happy with your lot. And know that your God who imparts knowledge to man has bestowed His love on you. When you will become adept in choosing this kind of life, and you will repeat it several times until you will be successful in it, strengthen yourself, and you will choose another path even higher than this.[38]

Sebbene esista una varietà di pratiche che incorporano il movimento con la ripetizione di frasi o parole, nessuna occupa le facoltà intellettuali della mente con così tante attività sul cambiamento degli oggetti, combinate con il coinvolgimento vocale e corporeo. Ciò che rende unico il sistema di combinazione delle lettere proposto da Abulafia è che la combinazione di così tanti oggetti (lettere, vocali, parole, movimenti fisici e respiri) richiede una memoria straordinaria. Idel sottolinea che questo sistema non consente periodi prolungati di contemplazione, ma piuttosto “short bursts into eternal life, followed by a rapid return to the life of this world”.[39] Idel commenta alcuni aspetti insoliti del sistema di Abulafia:

La complessità di questo sistema può essere illustrata esaminando il processo di combinazione delle lettere. Quando si lavora con una lettera ebraica è necessario combinarla con le lettere del nome esplicito di Dio (YHWH). Ogni lettera è combinata con il nome esplicito utilizzando ciascuna delle cinque vocali dell'alfabeto ebraico. Ad esempio, quando si usa la prima lettera aleph, essa viene unita a ciascuna lettera di YHWH, in modo che ci siano quattro combinazioni, AY, AH, AW, AH. Ciascuna di queste è poi vocalizzata con ogni possibile permutazione delle cinque vocali, holam, kamats, hirik, tserei, kubuts.

C'erano istruzioni specifiche su quanti respiri fare tra ciascuna combinazione di lettere, indicazioni specifiche su quanto tempo i respiri dovrebbero durare durante l'espirazione mentre si recita una particolare combinazione di lettere/vocali e come i movimenti della testa e delle mani dovrebbero essere coordinati con quanto sopra. Inoltre, Abulafia istruì i suoi seguaci a vedere le lettere come un'esperienza visionaria, sia come i nomi stessi di Dio sia sotto forma di un uomo, a simboleggiare l'essere divino.

In teoria, come scrive un autore, una sessione di meditazione poteva durare più di un giorno se qualcuno riusciva a farlo, e se commettevi un errore nel respiro, mano o suono, dovevi ricominciare da capo. Era molto pericoloso non cominciare dall'inizio, secondo Abulafia.

Per quanto complesso e difficile possa sembrare questo sistema, Abulafia ebbe diversi discepoli che ne attestarono l'efficacia. Ad esempio, nell'opera anonima scritta nel 1295 chiamata Sha'arei tsedek (Porte della Virtù), uno dei discepoli di Abulafia discute le idee basilari della Cabala profetica e descrive gli altri due metodi con cui cercò di ottenere "l'espansione spirituale": il metodo della “cancellazione” praticato dai mistici musulmani e il metodo della filosofia razionalista, fino ad arrivare finalmente alla Cabala e al sentiero dei nomi, attraverso il quale raggiunse il livello spirituale che desiderava. Una breve selezione che descrive la sua esperienza di luce interiore è stata citata precedentemente. La selezione completa, inclusa nell'Appendice 4, fornisce un resoconto rivelatore della sua relazione con il suo maestro e dei suoi progressi nel portare la sua anima oltre il reame fisico e riempirla con l'influsso divino.

Le tecniche di Abulafia furono adottate e incorporate anche nelle pratiche successive del misticismo ebraico. I mistici ebrei sufi originari dell'Egitto continuarono a vivere in Terra Santa durante il tempo di Abulafia; si pensa che incorporassero elementi dei suoi insegnamenti e producessero una sorta di Kabbalah sufi ibrida. L'influenza di Abulafia si fece sentire anche tra cabalisti come Isaac di Akko e Shem Tov ibn Gaon nel XIV secolo, e perfino negli insegnamenti dei mistici di Safed del XVI secolo come Moses Cordovero e Hayim Vital.

Note

[modifica | modifica sorgente]| Per approfondire, vedi Serie misticismo ebraico, Serie delle interpretazioni e Serie maimonidea. |

- ↑ Citato in Avraham Zacuto, Sefer ha-yuhasin, e riportato in Matt, trad., Zohar: Book of Enlightenment, pp. 3–4. Riferimento anche ad una traduzione del testo originale di Zacuto in Tishby, Wisdom of the Zohar, vol. i, Introduzione, pp. 13–17.

- ↑ “Contemporary scholarship on the Zohar (here we are indebted especially to the pioneering work of Yehuda Liebes and its more recent development by Ronit Meroz) has parted company with Scholem on the question of single authorship. While it is tacitly accepted that de León did either write long or edit long sections of the Zohar including the main narrative-homiletical body of the text, he is not thought to be the only writer involved. Multiple layers of literary creativity can be discerned within the text. It may be that the Zohar should be seen as the product of a school of mystical practitioners and writers, one that could have existed even before 1270 and continued into the early years of the fourteenth century.” (Green & Fine, Guide To The Zohar, p. 166.)

- ↑ Tutti gli stralci dai testi di de León sono presi dalle traduzioni originali in lingua inglese in Zohar: Book of Enlightenment di Matt, di Sperling & Simon, di Tishby, et al.

- ↑ Cfr. anche Moses de León, Or zaru’a, Alexander Altmann, cur., Qovez al yad, n.s. 9 (1980): 249. Cit. in Matt, trad., Zohar: Book of Enlightenment, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Green, prefazione a Matt, trad., Zohar: Book of Enlightenment, p. xiii.

- ↑ Hellner-Eshed, Language of Mystical Experience in the Zohar: The Zohar Through Its own Eyes, Hebrew university, 2000, p. 19. Citato in Green & Fine, Guide to the Zohar, p. 69. Trad (EN) pubbl. come A River Flows in Eden: The Language of Mystical Experience in the Zohar.

- ↑ Zohar 3:152b, Sperling & Simon, trad., The Zohar, vol. V, p. 211.

- ↑ Zohar 1:5a, Sperling & Simon, trad., The Zohar, vol. I, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Zohar 1:11a, Sperling & Simon, trad., The Zohar, vol. I, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Zohar 3:36a, Sperling & Simon, trad., The Zohar, vol. IV, p. 395.

- ↑ "Throughout Jewish history, back to the time of the merkavah mystics, we find the fellowship of mystics sitting in an idra, which is the Greek word for a semi-circle. In fact, the term is used in the Zohar for the important subdivisions of text, suggesting the fellowship and its pattern of interaction that produced the text, such as idra zuta (small idra), and idra rabba (large idra). Kabbalists in later periods even called their fellowships benei idra (companions of the idra). (Hallamish, Introduction to the Kabbalah, p. 61.)

- ↑ Green & Fine, Guide to the Zohar, p. 72. Corsivo nell'originale.

- ↑ Zohar 3:79b, in Tishby, Wisdom of the Zohar, vol. 1, p. 150.

- ↑ Schachter-Shalomi, Spiritual Intimacy, p. 12.

- ↑ Zohar 2:149a, in Tishby, Wisdom of the Zohar, vol. 1, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Zohar 2:14a–15a, Midrash ha‑ne’elam, in Tishby, Wisdom of the Zohar, vol. 1, p. 134.

- ↑ Zohar 2:14a–15a, Midrash ha‑ne’elam, in Tishby, Wisdom of the Zohar, vol. 1, pp. 134–35.

- ↑ Zohar 2:14a–15a, Midrash ha-ne’elam, in Tishby, Wisdom of the Zohar, vol. 1, p. 131.

- ↑ Zohar 3:287b–288a, Idra zuta, in Tishby, Wisdom of the Zohar, vol. 1, p. 162.

- ↑ Zohar 3:144a–144b, Idra rabba, in Tishby, Wisdom of the Zohar, vol. 1, p. 159. Chiamandolo “Sabbath,” lo paragona al settimo giorno della settimana che illumina con la sua santità gli altri giorni.

- ↑ Zohar 3:296b, Idra zuta, in Tishby, Wisdom of the Zohar, vol. 1, p. 164.

- ↑ Zohar 1:216b–217a, in Tishby, Wisdom of the Zohar, vol. 1, p. 165.

- ↑ Zohar 1:216b–217a, in Tishby, Wisdom of the Zohar, vol. 1, p. 166.

- ↑ Nuna significa pesce. Tramite un gioco di parole, sta dicendo che suo padre è Rabbi Hamnuna Sava, il successore di Rabbi Simeon.

- ↑ Zohar 1:5a–7a, in Tishby, Wisdom of the Zohar, vol. 1, pp. 173–174.

- ↑ Wolfson, “From Mystic to Prophet”, estratto da “Jewish Mysticism: A Philosophical Overview,” in History of Jewish Philosophy, Frank & Leaman, curr., rist. sul sito <http://www.myjewishlearning.com>.

- ↑ La conquista del regno settentrionale di Israele da parte degli Assiri nell'VIII secolo AEV portò alla dispersione delle dieci tribù israelite che vivevano lì. La fede nel Messia nel Medioevo era legata al ritorno delle Dieci Tribù Perdute.

- ↑ La Guida di Maimonide fu un tentativo di armonizzare l'ebraismo e la filosofia per l'élite intellettuale dell'epoca ed è quindi scritta in modo tale che i suoi significati e le sue implicazioni più profondi non vengano colti dal lettore medio. Spesso, le idee sono espresse in modo intermittente e breve, in modo che il lettore debba collegare elementi di pensiero da una varietà di parti del testo prima di comprendere veramente l'idea che Maimonide sta presentando.

- ↑ Come discusso in precedenza nella sezione su Maimonide, il termine Intelletto non si riferisce a una funzione intellettuale o mentale come viene usato oggi. Nel medioevo, i filosofi e i mistici ebrei furono fortemente influenzati dai filosofi musulmani che a loro volta furono influenzati da Aristotele. Per loro l'Intelletto denota una facoltà spirituale emanante dal reame divino e inerente, in potenziale, agli esseri umani.

- ↑ Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, p. 131.

- ↑ Come la parola “intelletto”, negli scritti di Abulafia anche la parola “immaginazione” ha una varietà di significati a seconda del contesto. Qui Abulafia usa la parola “intelletto” per denotare la forza di volontà come atto intellettuale di controllo dei desideri. “Immaginazione” qui viene usata per indicare la miriade di desideri della mente.

- ↑ Idel, Mystical Experience in Abraham Abulafia, p. 143.

- ↑ Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, p. 133.

- ↑ Cit. in Jacobs, Schocken Book of Jewish Mystical Testimonies, p. 84. Questo brano viene citato anche in Idel, Mystical Experience in Abraham Abulafia, p. 79.

- ↑ Corretto secondo il MS. New York – JTS 1887, e MS. Cambridge Add. 644, cit. in Idel, Mystical Experience in Abraham Abulafia, p. 83.

- ↑ Da qui in poi, riporto fedelmente i testi (EN) stralciati da Scholem, Ha-kabbalah shel sefer ha-temunah ve-shel Avraham Abulafia (The Kabbalah of the Book of the Figure and of Abraham Abulafia) e da Idel, Mystical Experience in Abraham Abulafia.

- ↑ Citato in Scholem, Ha-kabbalah shel sefer ha-temunah ve-shel Avraham Abulafia (The Kabbalah of the Book of the Figure and of Abraham Abulafia), J. Ben-Shlomo, cur., Gerusalemme 1965, p. 208; Bokser, trad., Jewish Mystical Tradition, pp. 104–105.

- ↑ MS. Oxford 1582, folio 52a, cit. in Scholem, Ha-kabbalah shel sefer ha-temunah ve-shel Avraham Abulafia, J. Ben-Shlomo, cur., Gerusalemme 1965, p. 210f.; cit. in Bokser, Jewish Mystical Tradition, pp. 99–101.

- ↑ Idel, Mystical Experience in Abraham Abulafia, p. 40.